Today is May 7th, and on this day in history, we commemorate National Paste Up Day—a quiet nod to a vanished craft that once defined how information reached our eyes. Before digital design tools transformed the landscape of visual communication, paste up artists worked through long nights with X-Acto knives, wax, rubber cement, and steady hands, piecing together the newspapers and magazines that would connect us.

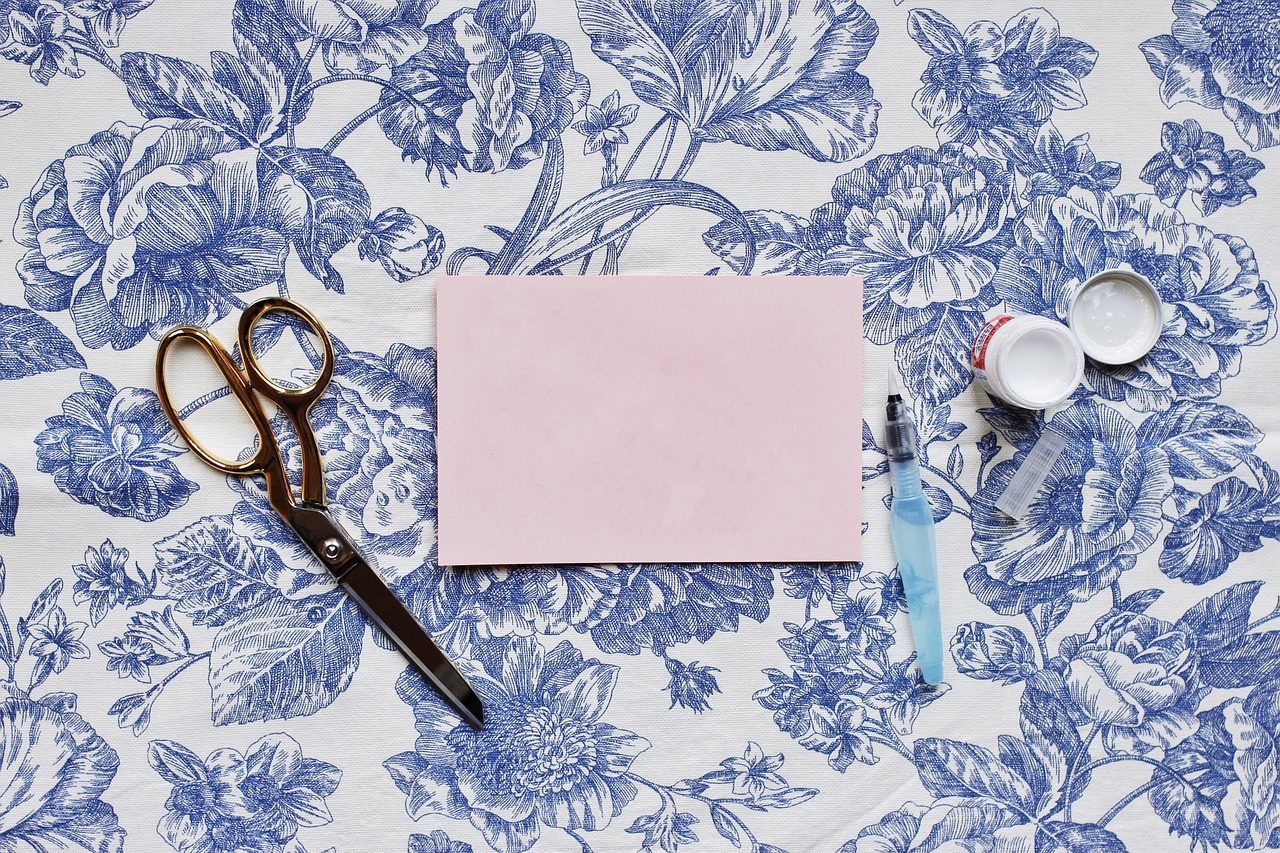

There’s something profound about physical creation—the way hands once touched every headline, every photograph, every column of text before it reached the public eye. These craftspeople worked in that liminal space between idea and physical manifestation, turning abstract concepts into tactile reality through careful arrangement and meticulous attention.

In the shadow of a single paste up board, you could trace the entire story of human communication. The primitive impulse to arrange symbols that began with cave paintings evolved through illuminated manuscripts, letterpress printing, and finally to these paste up artists sitting under bright lights, squinting at column widths and kerning pairs, making minute adjustments invisible to most readers but essential to the whole.

What happens when a craft disappears? Not dramatically, not with protest or memorial, but slowly, through technological obsolescence. The muscle memory of thousands of artists—how to cut a clean line, how to achieve perfect alignment without digital guides—evaporates like morning dew. Knowledge that passed from mentor to apprentice for generations now exists primarily in aging hands that remember the feel of the tools.

We live surrounded by ghosts of obsolete expertise. The cobbler’s knowledge of leather, the switchboard operator’s nimble connections, the paste up artist’s spatial intuition—all pushed aside by the relentless march toward efficiency. Each transition leaves behind a particular way of seeing and understanding the world.

When we touch our screens today, summoning information with frictionless ease, we stand on the shoulders of those who once physically constructed our visual reality piece by piece. The newspapers announcing moon landings, wars, and cultural revolutions passed through paste up artists’ hands before reaching history books.

Perhaps what we’ve gained in speed, we’ve lost in connection—to the physical world, to the human touch evident in slight imperfections, to the understanding that comes from working within material constraints.

As the sun rises on another May 7th, somewhere an aging paste up artist might run a thumb along the edge of a table, muscle memory recalling the resistance of an X-Acto blade against a metal ruler. In that moment, the past briefly inhabits the present—a small remembrance of hands that once shaped how we saw the world.